Frontend Architecture in 2026: How to Build Projects That Don’t Rot from the Inside Out

Frontend development didn’t become difficult because of React, Vue, or AI integration. It became more difficult because teams kept sending out features faster than they could build the structures. The result? A codebase that works – until they don’t. Then every change becomes a minefield.

If you’ve ever opened a project and wondered, “Who made this, and why do they hate me?”, then this article is for you.

We are going to talk about real frontend architecture. Not folder aesthetics. Not a framework fanfiction. The real structural decisions that determine whether your project scales cleanly or collapses under its own weight.

No fluff. No worship tools. Just principles that survive framework cycles.

The State of Frontend in 2026: A Reality Check

Let’s get one thing straight: Frontend today is not “just UI”.

Modern apps handle:

- Real-time data streams

- Offline-first synchronization

- AI-assisted workflows

- Cross-platform UI (web, desktop, mobile)

- Permission systems

- Complex caching layers

- Edge-deployed backends

If you’re still structuring projects like it’s 2018 – a component folder and vibes – you’re setting yourself up for a slow death through technical debt.

Frameworks changed. Complexity changed. Architecture needs to change too.

But here’s the uncomfortable truth:

Most frontend codebases fail for human reasons, not technical ones.

People rush.

People guess.

People procrastinate on structure.

People avoid refactoring.

People copy-paste patterns they don’t understand.

Architecture is not about perfection. It’s about damage control. You are deciding where chaos is allowed – and where it is not.

Why Frontend Projects Become Unmaintainable

Bad architecture rarely starts out badly. It starts out “temporarily.”

- “We’ll refactor later.”

- “Let’s put it in the page for now.”

- “We only need one version.”

- “We’ll modularize when it grows.”

Then never comes.

Then one day:

- A button change breaks three pages

- API logic is duplicated six times

- A junior developer is afraid to touch anything

- Testing seems impossible

- Release slows down

- Bugs slip through

This is not a tooling problem. This is a structural problem.

Three failure patterns appear everywhere.

1. God component

One file does:

- Getting data

- Transformation

- Validation

- UI rendering

- Error handling

- Side effects

It grows to 400-800 lines. No one understands the full flow. You’ve created a single point of failure.

2. The “Everything is Shared” Fallacy

Developers fear duplication, so they prematurely pull everything out:

- One global services folder

- One global hooks folder

- One global utilities folder

Soon nothing remains anywhere. Every feature imports from everywhere. Changing one function breaks unrelated flows. Congratulations – you’ve made spaghetti with TypeScript.

3. Root-nesting rabbit hole

Folders reflect URL paths very aggressively:

pages/

admin/

dashboard/

settings/

profile/Then you will need a profile avatar in the top navigation. Where does it live now? Copy-paste or deep import gymnastics. Either way, the structure loses meaning.

The real root cause: UI-centric thinking

Most frontend developers unconsciously consider the UI to be the “core” of the application. They build everything, starting with pages and components.

That’s the backend.

The UI is the outer shell. The volatile layer. The part that changes the most. If your business logic lives inside the UI, every redesign becomes a refactoring nightmare.

The right model:

Business logic → data orchestration → presentation

Not the other way around.

If your core logic can’t survive a UI rewrite, your architecture is fragile.

Three principles that really matter

Forget the rigid folder system. Forget the Twitter arguments. If you consider these three, everything else becomes easy.

1. Prediction

A developer should be able to figure out any feature logic in less than 10 seconds.

If someone asks, “Where is password reset handled?” and the answer is “uhhh search for it”, your structure failed.

2. Encapsulation

Each feature has its own logic. Other facilities do not reach inside it. Communication occurs only through the defined interface.

If deleting a folder breaks half the application, the encapsulation is broken.

3. Change proximity

Files that change together should stay together.

If changing the checkout validation requires editing five remote folders, the structure is wrong with you.

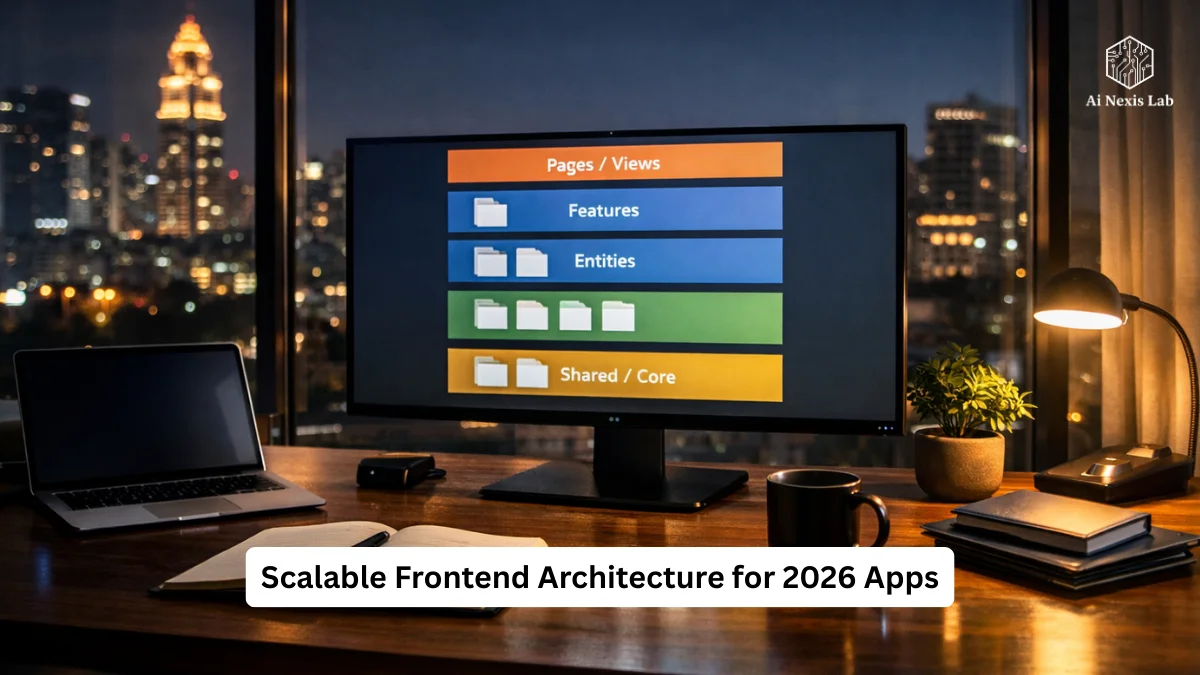

An Architecture Model That Actually Works in 2026

By now, most large-scale frontend teams converge towards a domain or feature-based organization. The names vary – feature-sliced design, domain-driven frontend, vertical slices – but the idea is the same:

Group code by business capability, not technical type.

Instead:

components/

hooks/

services/

utils/You structure:

features/

auth/

checkout/

search/

entities/

shared/

pages/This reflects how product teams think, how roadmaps are developed, and how bugs are reported.

If the product says “Checkout is broken,” you know exactly where to look.

A Practical Layered Structure

Let’s break it down into real terms.

Shared Layer

This is your foundation.

Contains:

- UI primitives (buttons, inputs, modals)

- Design tokens / themes

- Generic utilities

- Base API client

- Generic hooks (debounce, localStorage helpers)

Rules:

Shared code knows nothing about business logic.

If your shared folder imports “auth” or “cart”, you have broken the rule.

Entities Layer

Entities represent key business objects.

Examples:

- User

- Product

- Order

- Subscription

Entities include:

- Type definitions

- Data normalization helpers

- Entity-specific UI fragments

- Entity-level data fetching

Entities do not handle workflow. They represent “things” in your system.

Features Layer

Features are user actions.

Examples:

- Login

- AddToCart

- UpdateProfile

- SubmitReview

- ProcessPayment

Each feature includes:

- UI for actions

- Hooks or services for logic

- API calls if specific to the feature

- Validation rules

- Feature-level state

The feature should be portable. You should be able to move it to another page without rewriting its internals.

Pages Layer

Pages compose the features and entities in a screen.

Pages:

- Orchestrate

- Wire data

- Handle layout

- Own routing

Pages should not contain business logic. If they are, you are returning to the God elements.

Three-Layer code separation (it really matters)

Forget theoretical MVC. In the frontend, the separation is simple:

Presentation layer

- Stateless UI

- Receives props

- Emits events

- No API calls

- No business rules

If you can’t test it by passing dummy props, it’s doing too much.

Logic Layer

- Hooks or Services

- State Transitions

- Validation

- AI Prompt Construction

- Decision-Making

This layer is UI-agnostic. If tomorrow you replace React with a CLI or a native app, this logic will still make sense.

Data Layer

- API Calls

- Caching

- Persistence

- Synchronization

- Query Libraries (TenStack Query, RTK Query, Custom Features)

This layer knows nothing about the UI.

If one layer leaks into another layer, maintenance costs increase over time.

Naming Traditions: Not Cosmetic – Structural

Bad naming is no small inconvenience. It is a cognitive tax on every developer who joins the project.

Here’s what actually works:

Folders: kebab-case

Components: PascalCase

Hooks: useSomething

Functions: verb-first

Boolean: is/has/can

Constants: SCREAMING_SNAKE_CASE

Types: PascalCase

But more important than case style:

Names should reflect business meaning, not technical role.

Bad:useDataFetcher.ts

Good:useCheckoutSummary.ts

The first one doesn’t tell you anything. The second tells you where it is and why it exists.

Refactoring the real mess

Before

ProductPage.tsx does:

- Get the product

- Get reviews

- Format the price

- Handle add-to-cart

- Handle wishlist

- Manage loading and error conditions

- Render 600 lines of JSX

Testing is a pain. Reusability is impossible. Debugging is slow.

After

entities/product/

model/

product.types.ts

product.api.ts

ui/

ProductGallery.tsx

ProductSpecs.tsx

features/add-to-cart/

model/

useAddToCart.ts

ui/

AddToCartButton.tsx

pages/product/

ProductPage.tsxNow:

- Entity owns product data logic

- Feature owns cart logic

- Page orchestration

- UI components stay small

- Logic can be tested

- Future redesigns are cheap

This is the difference between “working code” and “scalable code”.

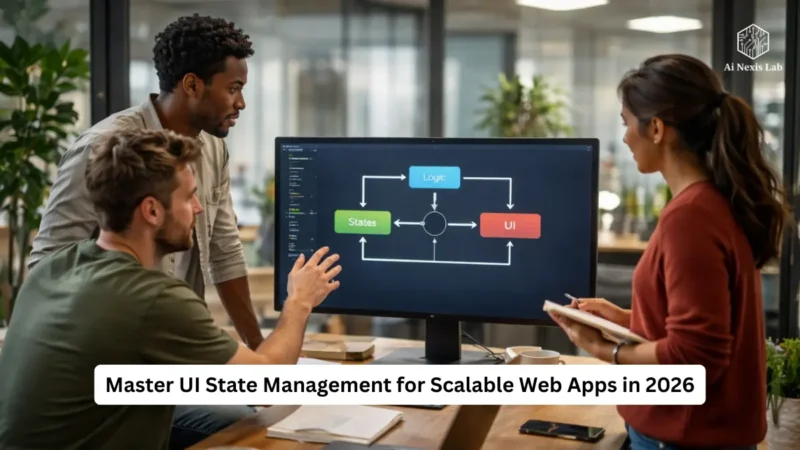

State Management in 2026: Reality, Not Fads

Here’s the current consensus among mature teams:

- Server State → Handled by query libraries or framework loaders

- Local UI State → Use component state

- Cross-feature client state → Only when actually shared

Global stores are no longer the default. They are tools of last resort.

If everything is global, nothing is predictable.

Modern rule:

Keep the state as close as possible to where it is used.

If two pages don’t need the same state, it shouldn’t reside in the global store.

Testing Strategy That Doesn’t Waste Time

Bad Testing Strategy:

- Snapshot Everything

- Test Implementation Details

- Break Every Refactor Test

Good Testing Strategy:

- Test Logic Layers in Isolation

- Test Critical User Flow

- Avoid Testing Trivial Presentational Components

If your tests break every time you change the name of a prop, your tests are testing the wrong thing.

Performance Architecture: The Silent Killer

Bad architecture kills performance:

- Unnecessary rerenders

- Duplicated API calls

- Overfetching

- Huge bundles

- Deep import chains

Good architecture naturally enables:

- Code separation by feature

- Lazy loading pages

- Predictive caching

- Tree-shuffleable shared modules

Performance is not something you “optimize later”. It is designed in advance by how you group the code.

AI Integration: The New Complexity Layer

By 2026, AI features are common:

- Chat interfaces

- Prompt builders

- Suggestion engines

- Content generators

Trap:

Developers place prompt logic directly inside UI elements.

Improvement:

Treat AI prompt construction as logic-layer services.

UI passes intent → Logic builds prompt → Data layer calls AI API → UI renders result.

If your UI contains raw prompt strings, you have hard-coded product behavior into the presentation. That will hurt later.

Accessibility: No Longer Optional

Modern legal and product requirements demand accessibility from day one.

Architecture Impact:

- Shared UI primitives should implement semantic HTML

- Features should not bypass base components

- Pages should compose accessible building blocks

If accessibility is an afterthought, retrofitting becomes expensive and messy.

Linting, Formatting, and Bounds

Tooling is not architecture – but it enforces architecture.

Essentials for serious projects:

- ESLint with import boundary rules

- Prettier

- Path aliases

- Barrel file policy

- Forbidden deep imports

The goal is simple:

Make it easier to do the right thing than the wrong thing.

Common beliefs that still waste time

“We’ll refactor later”

No, you won’t. Once a feature ships, the pressure shifts to the next one. Refactoring only happens when the product breaks.

“We need a common system for everything”

No. Abstractions should appear after iteration, not before.

“Folder structure is the same as architecture”

No. Architecture is the dependency direction, not the folder tree.

“Framework X solves architecture”

No framework solves bad boundaries.

A Startup Checklist That Actually Works

- Define Shared UI Primitives First

- Define Entity Models

- Define Feature Slices

- Enforce Import Boundaries

- Keep Logic Out of the UI

- Avoid Global State Unless Proven Necessary

- Test Logic, Not Markup

- Keep Names Business-Based

- Review Structure in Every PR

If you do this, your codebase won’t be perfect – but it will survive.

Long-Term Mindset

The goal of architecture today isn’t to write code quickly.

They are:

- Add features without fear next year

- Onboard new developers quickly

- Refactor safely

- Reduce bug risk

- Avoid rewrite cycles

Good architecture is boring. Predictable. Unpredictable.

Bad architecture is exciting – until it happens.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: How big should a feature folder be?

A: As big as needed. If a feature gets too big, it’s likely to have multiple features. Divide by user action, not by technical concern.

Q: Should I use feature-sliced design as documented?

A: Use principles, not dogma. Adapt level names to your team’s language. Boundaries are more important than folder names.

Q: Do I need a Global State Manager in every project?

A: No. Most applications can run with local state + server-state caching. Introduce global state only when multiple remote facilities truly need shared reactive data.

Q: Is TypeScript mandatory?

A: For any serious project: Yes. Without static typing, large-scale refactoring becomes a gamble.

Q: Where do API calls belong?

A: Close to the domain they serve. If an API is used only by a checkout, it resides in the checkout or its related entity. Becomes a huge global api.ts dumping ground.

Q: Should UI components contain logic?

A: No. UI should reflect the state, not the management of business decisions. If a component has complex state trees, move the logic into hooks.

Q: How can deep import be prevented?

A: Use index (barrel) files as public APIs per slice. Apply ESLint through boundaries.

Q: What about monorepos?

A: Same principles. Each package becomes a bounded context. Shared UI libraries remain framework-agnostic whenever possible.

Q: Is this overkill for small projects?

A: No – because small projects grow. A lightweight framework early on prevents expensive rewrites later.

Q: How can I convince my team to adopt this?

A: Start by refactoring a feature slice. Let the results speak for themselves. The argument theory rarely works. Demonstrating a reduction in bug count works.

Q: Does this work outside of React?

A: Yes. The principles apply to Vue, Svelte, Solid, mobile, and non-UI apps as well. Frameworks change. Boundaries remain the same.

Final Words: Frontend Architecture is a choice you make every day

You don’t “finish” architecture. Every PR either improves the structure or ruins it.

There is no perfect system. There are only:

Code that fights against you

Code that helps you

Choose another.

And if you’re serious about building a frontend system that goes beyond the next redesign – start with boundaries, not folders.

Everything else follows.