Designing software that doesn’t break even after six months

Every developer starts a new project with optimism based on illusion.

Fresh repo. Clean folder structure. Beautiful architecture diagram. Tests pass. CI green. Everyone talks about scalability, flexibility, and “doing it right this time.”

Then reality sets in.

After three months, it takes five files to touch to add a checkbox. Six months later, something unrelated breaks to fix a small bug. A year later, someone says the cursed phrase:

“We might need to rewrite it.”

It’s not bad luck. It’s software decay – a slow structural failure caused by how humans build systems under pressure.

Software doesn’t suddenly break. It decays quietly. One shortcut at a time. One hasty decision. An undocumented solution. A “temporary” hack that becomes permanent.

By 2026, this problem is worse than ever. AI tools now allow teams to produce code that can also be reviewed much faster than previous generations. That speed is a double-edged sword: productivity skyrockets, but so does poorly thought-out architecture. We are generating technical debt at machine scale.

If you want your software to last more than two quarters, you have to design for change, not for the current Jira board.

This article is a tough, practical look at how to do it – without fairy tales, without silver bullets, and without pretending the framework will save you.

The six-month cliff is real

Most software projects follow a similar path:

Month 1:

Everything is clean. The abstractions look elegant. The developers are proud.

Month 3:

Feature requests are coming in faster than architecture discussions. Shortcuts appear. “We’ll refactor later.”

Month 6:

No one touches the main module without concern. It takes weeks to onboard new developers. Bugs appear in strange places. The system feels ghostly.

This is not because your team is bad. Because entropy always wins unless you actively fight it.

The inconvenient truth:

Most software is not designed. It is assembled under deadline pressure.

And assemblies deteriorate.

Why Software Really Rots

Let’s look at the vague explanations. Software rots for specific reasons.

1. Facility accumulation without structural maintenance

Each new facility increases system complexity. Not linearly – exponentially. Each feature adds new interactions, edge cases, dependencies, and states.

If you don’t invest in refactoring when adding features, complexity grows faster than comprehension. Ultimately, no one fully understands the system. That’s the tipping point.

By 2026, this problem becomes exponential, as AI code generators are writing complete features in minutes. Teams are shipping more code per sprint – but review, architecture thinking, and refactoring time hasn’t increased to match it.

The result: rapid decay.

2. Deadline-Based Shortcuts

Everyone takes shortcuts. Hardcoded values. Fast database queries. Copy-pasted logic. Skipped tests.

Each shortcut makes sense in isolation. Together, they create a minefield.

And here’s the harsh truth:

“We’ll clean it up later” is usually a lie.

Later never comes. New priorities replace old priorities. Shortcuts become part of the foundation. You build a house on wet cardboard.

3. Knowledge evaporation

People leave. Teams move. Contractors move on. Context disappears.

Code without context is just strange symbols. Without understanding why decisions were made, future developers work around the system with it.

That’s when the software becomes “legacy” – not because it’s old, but because no one dares to touch it.

4. External Dependency Flow

The API changes. Libraries deprecate. Cloud services are changing pricing models. SDKs drop support.

If your internal logic is tightly tied to external tools, external change becomes internal pain. Your architecture inherits the instability of everything you rely on.

By 2026, SaaS APIs are updated faster than most teams can adapt. If you are tightly coupled, you will rot by coupling.

Most teams design for today – not for change

The main mistake is not a lack of intelligence. It is a lack of time to think about change.

Developers like to solve problems immediately. Architecture is delayed gratification. When done right, it is invisible. No one appreciates clean boundaries during a sprint review. They appreciate shipped features.

But longevity requires one principle above all else:

Design your system so that parts can be replaced independently.

If changing one module changes five other modules, you’ve already lost.

Principle 1: Keep modules small and boring

Complicated modules look impressive. They are also fragile.

Durable modules:

- Have a responsibility

- Have clear input and output

- Avoid side effects

- Can be changed without touching unrelated code

If a file needs a comment explaining what it is doing, it is too complex. If a module requires reading three others to understand, it is poorly designed.

In 2026, the functional-core/imperial-shell pattern is mainstream for a reason. Pure logic remains static. Side-effect-heavy glue remains thin and replaceable.

Simple bits are smarter. Every time.

Principle 2: Separate static logic from volatile integration

Some parts of your system change constantly:

- UI

- Third-party APIs

- Payment providers

- Messaging services

- Analytics tools

Other parts change rarely:

- Business rules

- Domain models

- Validation logic

- Core workflow

Your goal is to prevent volatile parts from shaping static parts.

If your “order” logic knows about Stripe, your domain is corrupted. If your “user” model relies on Firebase SDK objects, your core is hostage to external changes.

Instead:

- Core logic speaks in abstract interfaces

- Integration implements those interfaces

- Wiring happens at the edge

When Stripe API versions change, you change an adapter. Not your entire checkout system.

This is not academic purity. This is how you avoid rewriting.

Principle 3: Prefer clear wiring over magic

Frameworks prefer “convention over configuration”. It seems productive until debugging starts.

Hidden reflection, auto-wiring, global registries, invisible dependency graphs – all of these reduce typing and increase confusion.

A system that requires a debugger session to understand data flow is a failed design.

Explicit dependency injection seems verbose. But verbosity buys clarity. And clarity buys maintainability.

If another developer can figure out the request path by reading the code instead of guessing the framework behavior, you’ve succeeded.

Principle 4: State Must Be Localized

Global state is the silent killer of large codebases.

Singletons. Static caches. Global configuration objects that change at runtime. Shared in memory stores.

They work – until they don’t. Then bugs become non-deterministic, tests become flaky, and behavior depends on execution order.

State includes:

- in function inputs

- in database records

- in explicitly owned objects

If state is everywhere, control is nowhere.

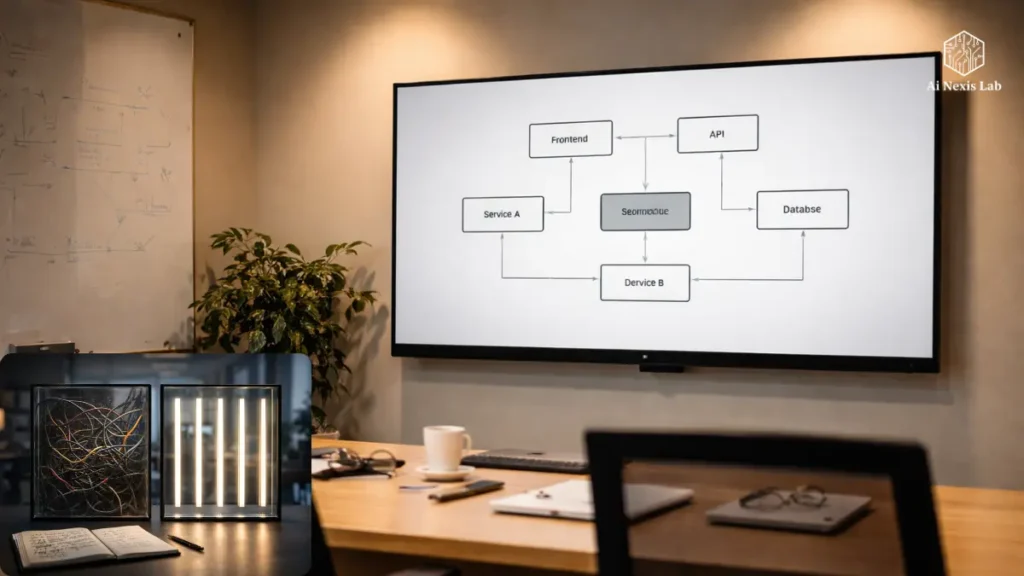

A Real-World Scenario: Notification Systems That Rot

Let’s walk through a common failure.

Month 1:

Requires email notifications.

You call SendGrid directly by writing NotificationService.sendEmail().

Month 3:

SMS required.

You add if(type == SMS) and call Twilio in the same service.

Month 5:

Need push notifications.

Add Firebase logic. More conditional.

Month 8:

Needs a scheduled digest.

The service now also features cron logic and batching.

Result:

- One 900-line god-class

- Impossible to test without mocking multiple APIs

- Any change risks breaking everything

This is not rare. It’s common.

Better approach:

NotificationDispatcherinterfaceEmailDispatcher,SMSDispatcher,PushDispatcher- The main logic loops through the enabled dispatchers

- Each dispatcher owns its integration

Now:

- Zero changes to existing code are required to add a new channel

- Tests remain separate

- External API changes are included

This is what modular design really looks like in practice.

Principle 5: Don’t Guess Future Requirements

A classic mistake: speculative abstraction.

“We might need multi-domain later.”

“We might need multi-tenancy later.”

“We might support more providers later.”

So teams build over-engineered frameworks before any real need exists. That complexity becomes dead weight.

The right approach:

- Solve today’s problem cleanly

- Keep boundaries flexible

- Don’t build pre-build features

- Build boundaries where change is likely

Flexibility beats predictability. Prediction is usually wrong.

Principle 6: Document why, not what

Code explains what. It never explains why.

Why did you choose an event-driven architecture?

Why did you denormalize that table?

Why did you reject the framework?

When that context disappears, future developers make conflicting decisions. Inconsistency creeps in. Structure dissolves.

Architecture Decision Records (ADRs) solve this cheaply. A simple Markdown file for logging key choices saves hundreds of hours later.

Not documenting the reasoning is professional negligence. Period.

Principle 7: Refactoring is not optional maintenance

If you never refactor, your system will fall apart. Guaranteed.

Refactoring is not a “nice to do”. It’s structural hygiene.

Healthy teams:

- Dedicate time in each sprint

- Treat refactoring as feature work

- Measure complexity trends

- Aggressively remove dead code

If your momentum drops because refactoring feels slow – your option is to rewrite later. Which is slow.

Modern Reality: AI Changes the Equation

By 2026, AI coding assistants will have become standard. They write tests, services, API clients, UI scaffolds in seconds.

But here’s the catch:

AI is great at generating code.

AI is terrible at global architectural decision making.

AI does not experience long-term pain. It doesn’t maintain systems. It doesn’t onboard new developers. It doesn’t debug production incidents at 2 AM.

That’s your job.

If you let AI generate features without applying architectural discipline, you accelerate decay. AI becomes a debt multiplier.

Use AI as a mason. You remain the architect.

Modular monoliths are winning

Other industry reforms happening by 2026:

Teams are moving away from premature microservices.

Microservices solve organizational scaling – not code quality. For most products, early microservices turn code complexity into network complexity. Same mess, more latency.

Modern best practices:

- Start with a modular monolith

- Enforce internal boundaries

- Extract services only when justified by load or team scaling

If you can’t design a clean monolith, you won’t design clean microservices either. You will only distribute chaos.

Resilience is part of longevity

Systems that collapse upon dependency failures are fragile.

External APIs go down. Networks glitch. Rate limits hit. Credentials expire.

If your software crashes instead of degrading gracefully, it is brittle.

Sustainable systems:

- Time out safely

- Retry responsibly

- Fail open or close intentionally

- Offer fallback paths

- Expose kill-switches for new features

Failure is not exceptional. It is expected. Design accordingly.

Your Anti-Rot Operating Checklist

Before committing to major changes, ask:

- Can I remove any code instead of adding more?

- Are the boundaries between core logic and integrations clear?

- Does any module do more than one job?

- Does any module know too much about external services?

- Is state leaking globally?

- Can another developer figure out the logic without reading the framework internals?

- Have we noticed why key decisions exist?

- Has time been allocated to refactor this sprint?

If the answer to many is “no” – your system is already aging faster than you think.

Common myths that waste teams’ time

“We’ll refactor after the MVP.”

No, you won’t. The MVP becomes the product. The product becomes sacred. Refactoring is postponed forever.

“The new structure will fix our architecture.”

Frameworks do not fix thinking. They just provide new ways to make a mess.

“Microservices solve scaling problems.”

They solve org scaling. They often make code complexity worse.

“We’ll hire senior developers later to clean it up.”

Senior developers avoid joining a disaster codebase. Good luck.

“AI will refactor it automatically.”

AI doesn’t own the system. Accountability can’t be automated.

What long-lived systems have in common

When you examine software that lasts for years – not months – you will always find:

- Clear domain boundaries

- Minimal coupling

- Clear dependencies

- Aggressive removal of used code

- Documented architectural logic

- A culture of continuous refactoring

- Conservative technology choices

- Stable core logic insulated from volatile integration

There is no magic. Just discipline.

How to start fixing an existing codebase

Pick a painful area. Not the whole system. One.

Then:

- Identify its true responsibility

- Remove irrelevant logic

- Extract interfaces at external boundaries

- Replace hidden dependencies with explicit ones

- Add tests around stable behavior

- Document why this framework exists

Small wins combine. Big rewrites fail.

The Hard Truth

If your codebase looks fragile after six months, it wasn’t bad luck. It was design debt.

Longevity doesn’t come from talent. It comes from refusing to lie to yourself about shortcuts.

You either pay for a consistent framework – or you pay for a rewrite later.

There’s no third option.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: How long should refactoring take per sprint?

A: At least 15-25%. If you can’t afford that, you can’t even afford to send the facilities – you’re just borrowing time from the future.

Q: Should we write an ADR for every decision?

A: No. Only decisions that affect structure, dependencies, data model, or technology choice. If it would be costly to reverse the decision later, document it.

Q: Will design patterns still be relevant in 2026?

A: Yes – but not as formal UML exercises. Patterns only become important when they facilitate change. If a pattern adds complexity without reducing coupling, drop it.

Q: How can we stop AI tools from making architectural messes?

A: Close the boundaries. Give the AI an interface contract. Review AI-generated code like junior developer output. AI follows the constraints – give it good code.

Q: When are microservices really justified?

A: When:

1) Teams are more than ~8-10 developers per domain

2) Independent scaling is required

3) Deployment independence provides real value

Not before.

Q: How to measure codebase health?

A:

1) Time to implement new features

2) Number of files touched per change

3) Onboarding time for new developers

4) Frequency of regression bugs

If it is trending upwards, decay is occurring.

Q: Is rewriting ever justified?

A: Rarely. Only when:

1) Domain understanding changes completely

2) Technology stack is unsupported

3) Refactoring cost exceeds rebuilding cost

Most rewrites fail because they quickly repeat old mistakes.

Q: What is the fastest way to fix a broken system?

A: Remove dead code. Remove unused features. Reduce surface area. Small systems are easier to fix.

Final Word

Software longevity is not about perfection. It’s about refusing to accumulate invisible damage.

Every shortcut has interest. Every undocumented decision creates confusion. Every hidden dependency creates fear.

If you want a system that lasts, design for change, keep things clear, be brutally honest about complexity, and constantly refactor.

No heroism. No rewrites. Just professional discipline.